Is Normal normal?

The rumor says that Normal distribution is everything.

It will take a long long time to talk about the Normal distribution thoroughly. However, today I will focus on a (seemingly) simple question, as is stated below:

If $X$ and $Y$ are univariate Normal random variables, will $X+Y$ also be Normal?

What’s your reaction towards this question? Well, at least for me, when I saw it I said “Oh, it’s stupid. Absolutely it is Normal. And what’s more, any linear combination of Normal random variables should be Normal.”

Then I’m wrong, and that’s why I want to write this blog.

A counter-example is given by the book Statistical Inference (George Casella and Roger L. Berger, 2nd Edition), in Excercise 4.47:

Let $X$ and $Y$ be independent $N(0,1)$ random variables, and define a new random variable $Z$ by

$$Z = \begin{cases} X &\text{if } XY > 0 \\ -X & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

Then it can be shown that $Z$ has a normal distribution, while $Y+Z$ is not.

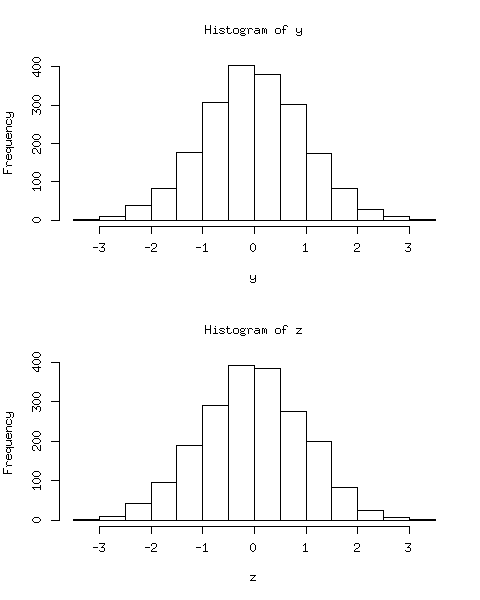

Here I will not put any analytical proof, but use some descriptive graphs to show this. Below is the R code to do the simulation.

set.seed(123);

x = rnorm(2000);

y = rnorm(2000);

z = ifelse(x * y > 0, x, -x);

par(mfrow = c(2, 1));

hist(y);

hist(z);

x11();

hist(y + z);

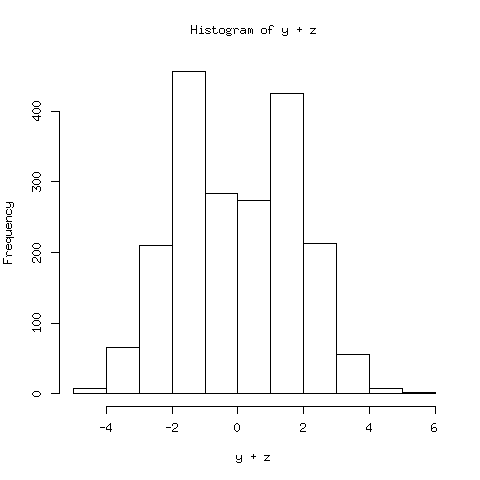

We obtain the random numbers of $X,Y$ and $Z$, and then use histograms to show their distributions.

The result is clear: Both $Y$ and $Z$ should be Normal, but $Y+Z$ has a two-mode distribution, which is obviously non-Normal.

So what’s wrong? It is not uncommon that we hear from somewhere, that linear combinations of Normal r.v.’s are also Normal, but we often omit an important condition: their joint distribution must be multivariate Normal. The formal proposition is stated below:

If $X$ follows a multivariate Normal distribution, then any linear combination of the elements of $X$ also follows a Normal distribution.

In our example, we can prove that the joint distribution of $(Y,Z)$ is not bivariate Normal, although the marginal distributions are Normal indeed.

Then you may wonder how to construct more examples like this, that is, $Y,Z$ are both $N(0,1)$ random variabels, but $(Y,Z)$ is not a bivariate Normal. This is an interesting question, and in fact, it’s much related to the Copula model. Here I only give some specific examples, while the details about Copula model may be provided in future posts.

Consider functions

$$C_1(u,v)=[\max(u^{-2}+v^{-2}-1,0)]^{-1 / 2}$$

$$C_2(u,v)=\exp(-[(\ln u)^2+(\ln v)^2]^{1 / 2})$$

$$C_3(u,v)=-\ln\left(1+\frac{(e^{-u}-1)(e^{-v}-1)}{e^{-1}-1}\right)$$

and use $\Phi(y)$ to denote the c.d.f. of $N(0,1)$ distribution, then $C_1(\Phi(y),\Phi(z))$, $C_2(\Phi(y),\Phi(z))$ and $C_3(\Phi(y),\Phi(z))$ are all joint distribution functions that satisfy 1) not bivariate Normal and 2) marginal distributions are $N(0,1)$.

Seems good, right?